West Antarctic Ice Sheet

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet is presently losing mass at an accelerating rate, but its response to a projected 2°C (3.5°F), or more, global warming remains a significant uncertainty in sea-level rise projections. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet is inherently more susceptible to collapse than the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, as it sits on land well below sea level, and its margin is exposed to a warming ocean. The submarine land surface on which the West Antarctic Ice Sheet sits deepens from the ice sheet margin towards its centre and has potential for runaway and unstoppable retreat. Of particular concern is that, if the large ice shelves at the edge of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, that help to hold the ice sheet in place collapse, ice flow increases and gravity ‘takes over’.

Currently, the Ross Ice Shelf acts as a buttress slowing the flow of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet into the ocean and limiting sea-level rise. If the ice shelf collapses, the ice sheet will follow and the rate and amount of sea-level rise will rapidly increase.

We are obviously grateful the ice shelf is there, and we certainly hope it remains, but it means we have to come up with innovative ways to access the hard-to-reach records. Dr Richard LevyCo-Chief Scientist

Our research aims to understand the timing of past Ross Ice Shelf collapse and West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat, and the local and regional environmental conditions that drove these changes during past warmer-than-present climatic conditions.

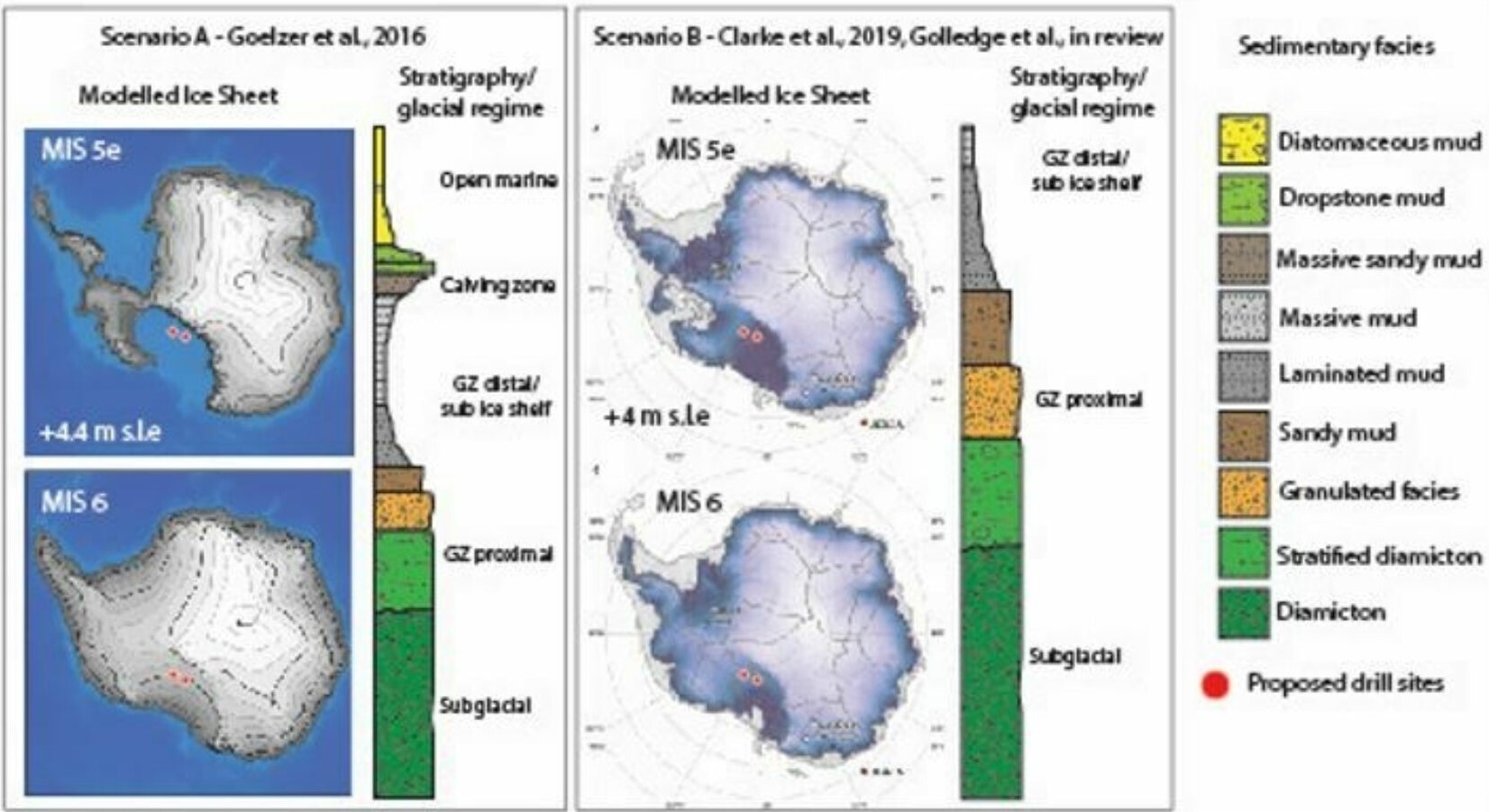

During the last interglacial period (129,000–116,000 years ago), global temperatures were 1°C (1.8°F) warmer than pre-industrial times. These temperatures are similar to those that now appear to be unavoidable to those we will see in the coming decades, even as we strive to reduce atmospheric carbon emissions. Due to ice melt, sea level was as much as 6–9 metres (20–30 feet) higher than present day. This extra freshwater in the ocean came from Earth’s large ice sheets, but it’s not yet clear how much came from Greenland and how much from Antarctica.

Long ago, when the Earth’s temperature was warmer than present, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet may have completely melted, and the Kamb Ice Stream site would have been covered by an open sea. Sediments that settled to the seafloor during these ice-free intervals likely included photosynthetic plankton (diatoms) that were flourishing in the open marine environment that occupied West Antarctica at the time.

Under previous colder-than-present climates – the last ice age – the West Antarctic Ice Sheet advanced across the site and laid down sediment called diamictite. This diamictite is characteristic of the depositional environment at the bottom of an ice sheet.

The SWAIS2C project will examine the results of sediment core drilling to identify any diatoms, which will tell us whether or not the West Antarctic Ice Sheet existed ~125,000 years ago.

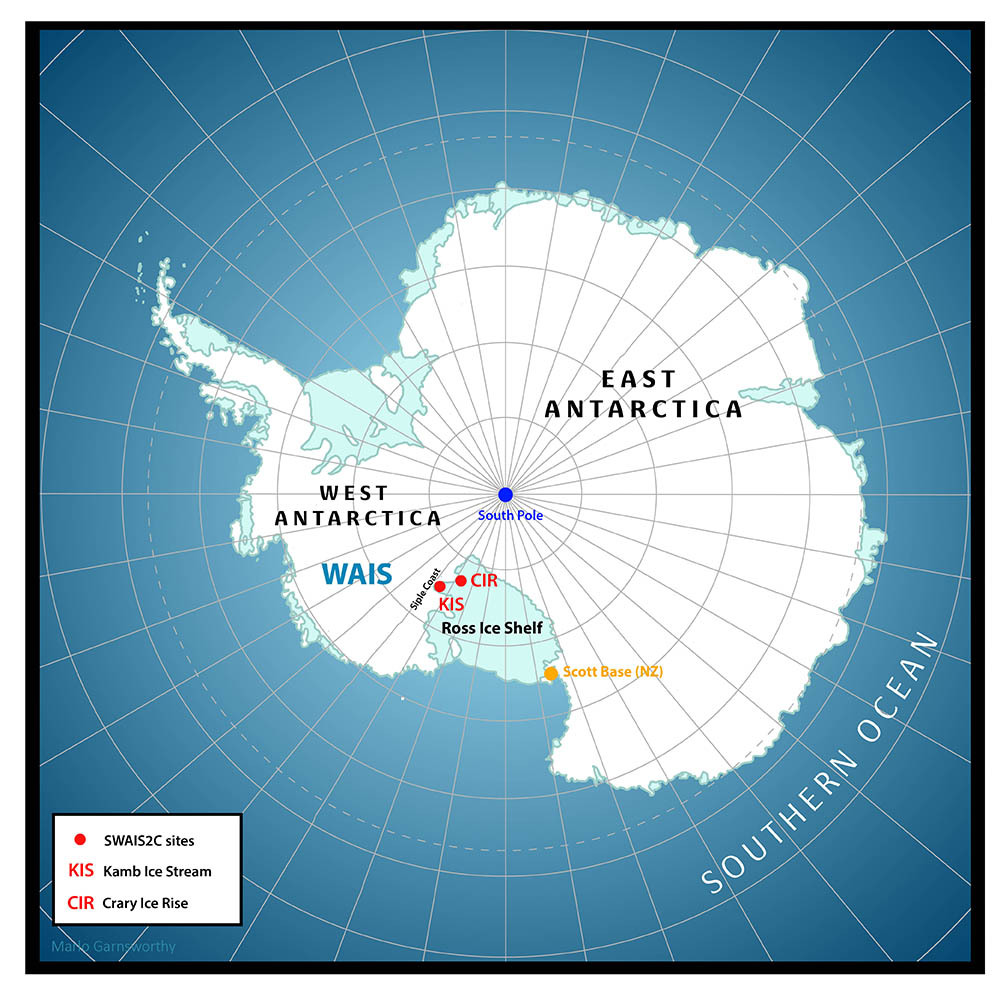

Our drill sites

**Kamb Ice Stream Site 3 or KIS-3 for short, where we need to drill through floating ice ~590 m thick, with an ocean cavity of ~30 m and Tidal range ~2 m. Lat. -82.628587°, Long. -156.304697°, or -82.628587° S, 156.304697° W **Crary Ice Rise Site 1 or CIR for short, where the ice is grounded and ~516 m thick with no ocean cavity, so no tidal compensation is required. Lat. -83.0301, Long. -172.668, or 83.0301 S, 172.668 W.